100 Years Later, See How the Great War Changed Art Forever

As Sotheby’s presents The Beautiful and Damned, a group of works created in the tumultuous years before and during the First World War, Kevin Jackson discovers why this was an important moment for art

Artists, wrote the American poet Ezra Pound not long before the outbreak of the Great War, are the “antennae of the race”: they see or sense what is coming long before the journalists and politicians. Pound’s maxim has often been mocked, but in the case of the early 20th century his contention seems well-founded. As early as 1909, the Italian Futurists – whose visual brilliance has long since outlived their ugly and foolish ideology – not only saw war coming but eagerly welcomed it. “We will glorify war”, their poet leader Marinetti bragged in the Futurist Manifesto, seeing military conflict as a means of purging a decadent Europe of its nostalgia, its democratic levelling and its softness, and of asserting noble masculine values. They would not have long to wait.

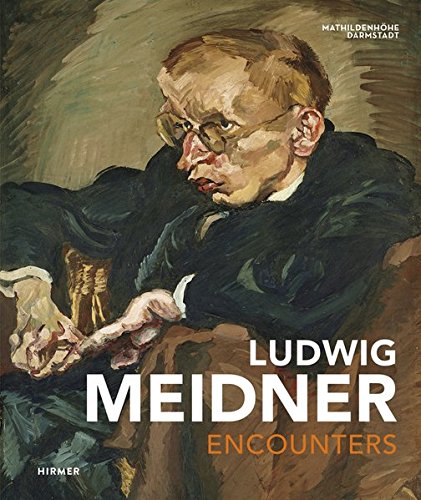

Ludwig Meidner, Apokalytpische Landschaft and Junger Mann mit Strohhut (Young Man with Straw Hat) – verso, 1912 $12,000,000–18,000,000

At the other extreme of the voices prophesying war was painter Ludwig Meidner, whose Apocalyptic Landscape series of 1912 was an eerily precise rendering of the horrors to come: skies torn apart by projectile-like comets, terrified figures fleeing from danger, buildings teetering on the brink of collapse, figures cramped and skewed with agony. It is an astonishing set of works, and Meidner never matched its scorching intensity.

Both Marinetti and Meidner should be borne in mind when thinking about the effect of the Great War on the arts. Cultural historians have often written of the astounding flowering of the arts after 1918 as – in large a reaction against the mass slaughter of the trenches – a counterpart to the exuberant mood among the affluent that made the 1920s known as the Jazz Age, or les années folles, or the Roaring Twenties. It was a spree that lasted until the Wall Street Crash of 1929. Bliss was it in that dawn to be alive, but to be in Paris with American currency was very heaven.

And yet this flowering had deeper roots – roots that went back to 1900 or earlier. In the arts, the first decade or so of the 20th century was the golden age of the “ism”: as well as Futurism (Italian and Russian), there was Expressionism (about 1905, though it had several important precursors), Fauvism, Cubism (created and developed by Picasso and Braque from 1909–14) Vorticism (largely Ezra Pound’s creation), Imagism, Pictorialism (in photography), all soon to be followed in the new USSR by Suprematism and Constructivism, a magical moment of creativity soon crushed under Stalin’s boots. In retrospect, we gather together all these disparate movements under the heading of Modernism.

Franz Marc, Kühe (Cows), 1 912. Estimate $1,500,000–2,000,000,

The only one of these major “isms” to be created after 1918 was Surrealism, officially created in 1924 by the poet André Breton who had served as a French Army doctor during the conflict and who had become fascinated by the neurotic and even insane soldiers he had treated. The irony of treating mad men at a time when millions of soldiers were being bombed, shot and gassed to death at the orders of confidently rational generals was not lost on Breton.

Surrealism was more than just another art movement: it was a gesture of violent protest against a civilisation that had eagerly embraced barbarism. Breton’s coterie enjoyed outraging decent opinion by saying “The War? Gave us a good laugh!” War apart, the other great influence on Breton was the most anarchic of all cultural revolutions, the Dada movement born in neutral Switzerland. Dada can be described in many ways – some commentators have even seen it as an occultist phenomenon – but its essence was an attack on order, reason, traditional art and language itself: all the Western virtues that had ended in the shambles of the Western front. Though it had only a few exponents – mainly Tristan Tzara, Hugo Ball and Hans Arp – its influence remains powerful to the present day.

The Dadaists were fortunate enough to be exempt from military service. Most other artists were not. The Great War was the first to be fought not by regular, standing armies alone, but by massive forces of conscripts; creative souls were as likely to be caught up in the draft as their neighbours, and some of them went eagerly into battle.

Otto Dix, one of the greatest modern German artists, and an ardent patriot who signed up as a gunner at the age of 23 in 1914, fought on both the Eastern and Western fronts and at the Somme, winning the Iron Cross for his gallantry. But he eventually sickened, and went on to create some the most terrifying images of armed conflict since Goya’s Disasters of War. He also created his own artistic movement, Neue Sachlichkeit; a sardonic, often grotesque form of visual satire. The American painter Marsden Hartley, now considered one of the major American artists of the earlier 20th century, had moved to Berlin in 1913, and became entranced by the military pageantry he saw there. The enchantment soon wore off when, as he put it, the romance of war gave way to a horrible reality.

Marsden Hartley, Pre-War Pageant , 1913

Modern warfare altered not only the characters of combatants, but the nature of war art. Before 1914, war art tended towards the likes of dramatic cavalry charges, tableaux of picturesquely dying generals and formal surrenders. The official artists of the First World War were more democratic (Tommy Atkins and his comrades in the lower were more typical subjects than Generals Haig or Foch), and more documentary, and they often used the new formal techniques they had been developing: Pound’s friend Wyndham Lewis, who served as a bombardier, produced Vorticist studies of artillery units, as did David Bomberg and William Roberts. Roberts went on to do some of the illustrations for TE Lawrence’s Seven Pillars of Wisdom, probably the greatest book to come out of the War. The one Vorticist sculptor, Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, was killed in action.

After war comes mourning, and remembrance. Ravel’s Le Tombeau de Couperin is a tribute to six of his friends who died in battle; Schoenberg’s Variations for Orchestra (1926-28) was partly inspired by his service in the Austrian Army. Writers of all nationalities, those who survived more or less intact, began to compose novels and memoirs: Henri Barbusse’s vehemently pacifist Under Fire, Ernst Jünger’s Storm of Steel, Erich Maria Remarque’s All Quiet on the Western Front and Robert Graves’s Goodbye to All That. Jünger apart, none of them believed that the great letting of blood had been anything other than monstrous folly. Ezra Pound spoke for many in his poem of 1919, High Selwyn Mauberley, which laments the deaths of “a myriad”, including “the best” of their generation, and bitterly contradicts Horace’s “Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori” (It is sweet and proper to die for one’s country). The art of the First World War has many faces, and cannot adequately be summed up in a simple formula or two, but perhaps its most important quality is minatory. It warns us about who we are.

![90[5].jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/50eb66f0e4b0033596299a41/1541433475700-VH1TDPY8EJB3EW3U32HT/90%5B5%5D.jpg)